3.1.7 Concept of values

Before discussing the different marine ecosystem services assessment and valuation tools, it seems important to question what the concept of values and how values can highly differ from one framework to another or from one person to another.

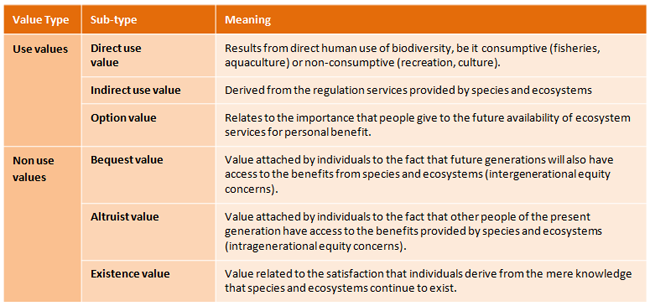

Table: Components of the Total Economic Value (TEEB 2010).

The United States Environmental Protection Agency Science Advisory Board discussed this issue in their report: “Valuing the Protection of Ecological Systems and Services: A Report of the EPA Science Advisory Board (EPA-SAB-09-012)” which examines ecological valuation practices, methods, and research needs at Environmental Protection Agency. Here is an extract of their discussion on this issue.

“People assign or hold all values. All values, regardless of how they are defined, reflect either explicitly or implicitly what the people assigning them care about. In addition, values can be defined only relative to a given individual or group. The value of an ecological change to one individual might be very different than its value to someone else.

Value is not a single, simple concept. People have material, moral, spiritual, aesthetic, and other interests, all of which can affect their thoughts, attitudes, and actions toward nature in general and, more specifically, toward ecosystems and the services they provide. Thus, when people talk about environmental values, the value of nature, or the values of ecological systems and services, they may have different things in mind that can relate to these different sources of value. Furthermore, experts trained in different disciplines (e.g., decision science, ecology, economics, philosophy, psychology) understand the concept of value in different ways. These differences create challenges for ecological valuations that seek to draw from and integrate insights from multiple disciplines.

A fundamental distinction can be made between those things that are valued as ends or goals and those things that are valued as means. To value something as a means is to value it for its usefulness in helping bring about an end or goal that is valued in its own right. Things or actions valued for their usefulness as means are said to have instrumental value. Alternatively, something can be valued for its own sake as an independent end or goal. While a possible goal is maximizing human well-being, one could envision a range of other possible social goals or ends including protecting biodiversity, sustainability, or protecting the health of children. Things valued as ends are sometimes said to have intrinsic value. This term has been used extensively in the philosophical literature but there is not general agreement on its exact definition.

Ecosystems can be valued both as independent ends or goals and as instrumental means to other ends or goals. This report therefore uses the term “value” broadly to include both values that stem from contributions to human well-being and values that reflect other considerations, such as social and civil norms (including rights), and moral and spiritual beliefs and commitments.

The broad definition of value used here extends beyond what are sometimes called the benefits derived from ecosystem services. Even the term “benefits,” however, means different things in different contexts. In some contexts (e.g., Millennium Ecosystem Assessment Board, 2003; Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, 2005), benefits refers to the contributions of ecosystem services to human well-being. In contrast, the term has a very precise meaning in the context of EPA regulatory impact analyses conducted under guidance from the U.S. Office of Management and Budget. In that context, benefits are defined by the economic concept of the willingness to pay for a good or service or willingness to accept compensation for its loss.

Given the many ways in which people think about value, the committee discussed a number of different concepts of value. [...] Although people assign or hold all values, preference-based values reflect individuals’ preferences across a variety of goods and services, including (but not limited to) ecosystems and their services. In contrast, biophysical values reflect contributions to explicit or implicit biophysical goals or standards determined to be important. The goal or standard might be chosen directly by decision makers or based on the preferences of the public or relevant groups of the public. Separating values into preference based and biophysical categories are not the only way to categorize values, but it has proven useful for the committee in understanding the various concepts of value used by different disciplines and how they are related.

[...] The task of distinguishing what is valued from the concept used to define the value is complex, regardless of the disciplinary perspective adopted. It requires clear, meaningful distinctions between the information available, perceptions of that information, and decisions or actions. Each discipline addresses these issues differently; these disciplinary differences are a potential source of confusion and miscommunication. So to make meaningful distinctions between these, the committee had to agree on a set of key assumptions. The resulting categorization of value concepts cannot be evaluated independent of these assumptions. [...]

The [following] concepts of value [...] differ in a number of important ways. Attitude or judgment-based values are based on empirically derived descriptive theories of human attitudes, preferences, and behaviour (e.g., Dietz et al., 2005). These values are not necessarily defined in terms of tradeoffs and are not typically constrained by income or prices, especially those that are outside the context of the specified assessment process. Rather, the values are derived from individuals’ judgments of relative importance, acceptability, or preferences across the array of changes in goods or services presented in the assessment. Preferences and judgments are often expressed through responses to surveys asking for choices, ratings, or other indicators of importance. The basis for judgments may be individual self-interest, community well-being, or accepted civic, ethical, or moral obligations.

Economic values

Economic values assume that individuals are rational and have well-defined and stable preferences over alternative outcomes, which are revealed through actual or stated choices (see, for example, Freeman, 2003). Economic values are based on utilitarianism and assume substitutability, i.e., that different combinations of goods and services can lead to equivalent levels of utility for an individual (broadly defined to allow both self-interest and altruism). They are defined in terms of the tradeoffs that individuals are willing to make, given the constraints they face. The economic value of a change in one good (or service) can be defined as the amount of another good that an individual with a given income is willing to give up in order to get the change in the first good. Alternatively, it can be defined as the change in the amount of the second good that would compensate the individual to forego the change in the first good. Economic values can include both use and non use values, and they can be applied to both market and non-market goods. The tradeoffs that define economic values need not be defined in monetary terms (willingness to pay or willingness to accept monetary compensation), although typically they are. Expressing economic values in monetary terms allows a direct comparison of the economic values of ecosystem services with the economic values of other services produced through environmental policy changes (e.g., effects on human health) and with the costs of those policies. However, monetary measures of economic values should not be confused with other monetized measures of economic output, such as the contribution of a given sector or resource to gross domestic product (GDP).

Community-based values

Community-based values are based on the assumption that, when consciously making choices about goods that might benefit the broader public, individuals make their choices based on what they think is good for society as a whole rather than what is good for them as individuals. In this case, individuals could place a positive value on a change that would reduce their own individual well-being (e.g., Jacobs, 1997; Costanza and Folke, 1997; Sagoff, 1998). In contrast to economic values, these values may not reflect tradeoffs that individuals are willing to make, given their income. Instead, an individual might express value in terms of the tradeoffs (perhaps, but not necessarily, in the form of monetary payment or compensation) that the person feels society as a whole – rather than an individual – should be willing to make.”

Values based on constructed preferences

Values based on constructed preferences reflect the view that, particularly when confronted with unfamiliar choice problems, individuals do not have well-formed preferences and hence values. This view is based on conclusions that some researchers have drawn from a body of empirical work addressing this issue (e.g., Gregory and Slovic, 1997; Lichtenstein and Slovic, 2006). It implies that simple statements of preferences or willingness to pay may be unstable (e.g., subject to preference reversals).12 Some have advocated using a structured or deliberative process as a way to help respondents construct their preferences and values [...]. This report refers to values arrived at by these processes as “constructed values.” The difference between economic values and constructed values can be likened to the difference between the work of an archaeologist and that of an architect (Gregory et al., 1993). Economic values assume preferences exist and simply need to be “discovered” (implying the analyst works as a type of archaeologist), while constructed values assume that preferences need to be built through the valuation process (similar to the work of an architect). As a result, the values expressed by individuals (or groups) engaged in a constructed-value process are expected to be influenced by the process itself. Constructed values can reflect both self-interest and community-based values. [...]

The committee considered all of these various concepts of value in its deliberations. To date, EPA analyses have primarily sought to measure economic values, as required by some statutes and executive orders [...]. However, the committee believes that information based on other concepts of value can also be an important input into Agency decisions affecting ecosystems. Recognizing the significance of multiple concepts of value is an important first step in valuing the protection of ecological systems and services.”